6.1 But it’s too small!

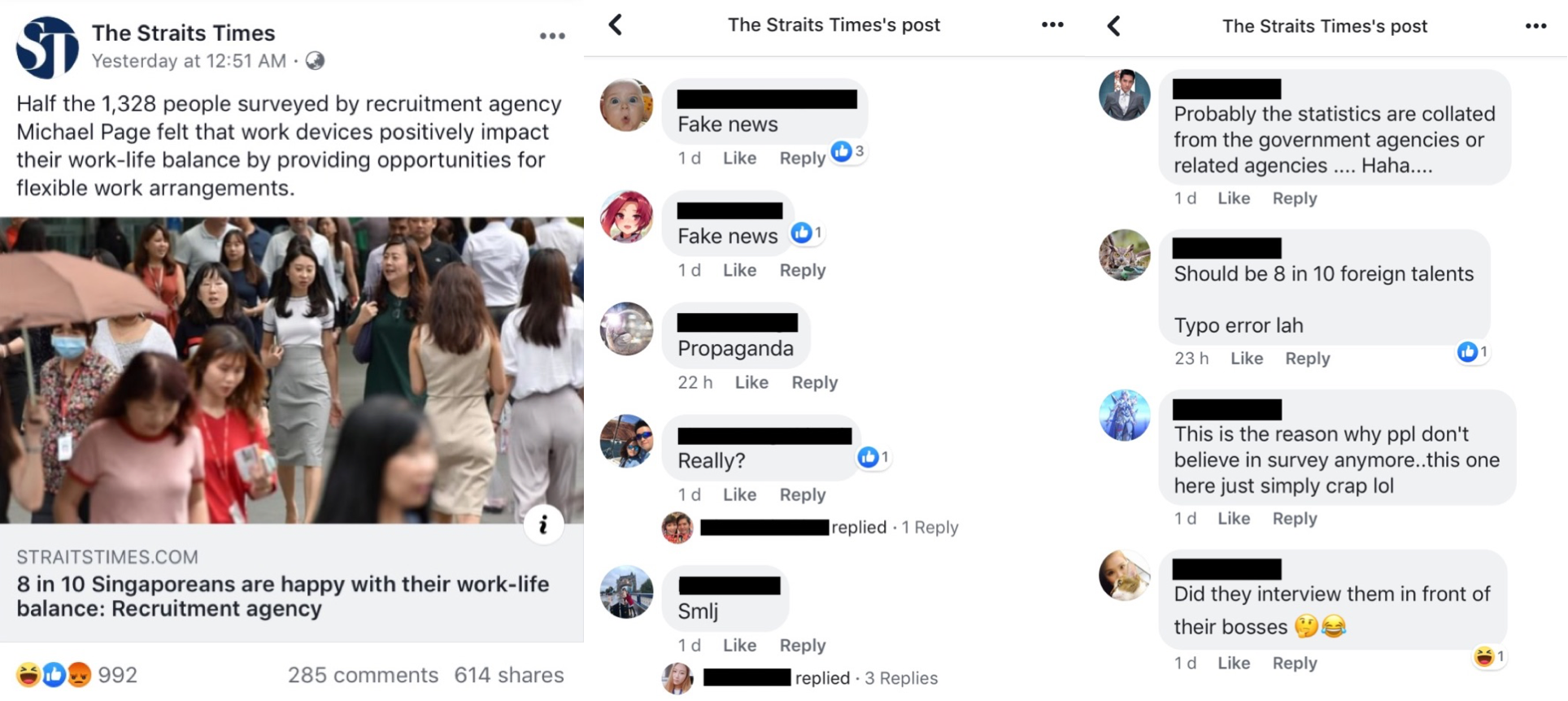

We will first look at an example. Local newspaper The Straits Times recently reported the findings of a study done by Michael Page, alleging that 8 of out 10 people are “happy” with their work-life balance.

Figure 6.1: Screenshot of online article on work-life balance. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

Many people on social media spoke out against the findings (not unexpectedly), questioning how reliable these findings were. These commentators probably felt such findings could not possibly reflect reality, given their own experiences. Surely, they might believe, more people are unhappy with their work-life balance. To rationalize this incongruence, there will inadvertently be some attention drawn to the sample size.

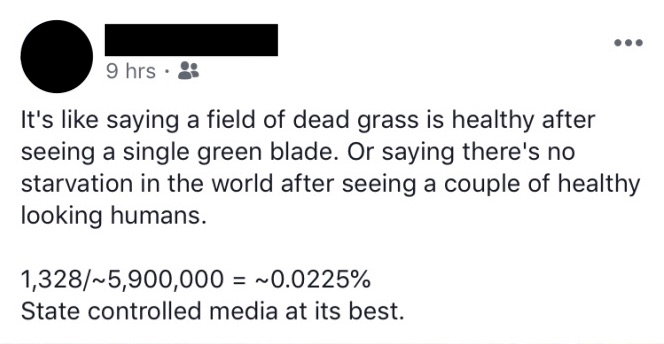

Figure 6.2: Screenshot of comment on work-life balance article. Retrieved July 16, 2019.

The comment above (Figure 6.2) shows how people often rationalize their feelings toward studies that don’t reflect their own perception32. How can 1328 survey respondents represent an entire population of approximately 5.9 million individuals?

The frustrating thing about the report by Michael Page is that it is not transparent about its methodology. Without this information, we cannot know for sure about how generalizable these findings are to the whole population. They likely cannot say much about all Singaporeans - the results may be limited to Singaporeans who took the survey, who may be a very different group of Singaporeans compared to those who did not take the survey.

This is not an isolated case - it often is difficult to find out exactly how surveys like these (that is, surveys aimed at generating public interest and reported by the media) were conducted. As we will see, the key questions are these: How were respondents recruited, and how is uncertainty being estimated?

For studies that do agree with the layperson’s perception, one probable response would be that it is “common sense” and that there is “no need to do a study to know this”.↩︎